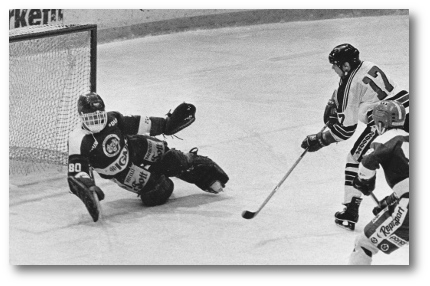

Ask a Finn about the “recent rise of great Finnish goaltenders” and he or she will be baffled.

The younger generation doesn’t understand the question because for them, Finland’s always produced great NHLers, such as Miikka Kiprusoff, Kari Lehtonen, Niklas Backström, Pekka Rinne, Antti Niemi and Tuukka Rask. Older fans think back to previous generations – Urpo Ylönen, Jarmo Myllys*, Kari Takko**, Markus Mattsson***, Jorma Valtonen, Hannu Kamppuri – and wonder what the fuss is about.

Good goalies have always been the trademark of Finnish hockey. Of the 22 stoppers who have represented Finland in the Olympics, 17 are eligible to be inducted into the Finnish Hall of Fame.

Fourteen are already in.

It wasn’t until 1967 that Finland beat any of the big nations in world play. That 3-1 win over Czechoslovakia was largely due to Ylönen’s play between the pipes. Three years later, in 1970, he was named best goalie at the worlds, the first Finnish player to gain that recognition.

But in 1969, “I was the worst goalie of the tournament,” he says. In the off-season, he got his knees fixed and decided to study for a Finnish federation coaching diploma, focusing only on goaltending.

In 2014, the 70-year-old Ylönen is considered the goaltending guru of Finland. In a few years in the 1990s, Kiprusoff, Markus Ketterer, Antero Niittymäki, Jani Hurme and Fredrik Norrena honed their craft under Ylönen in Turku, then left for the NHL, with varying degrees of success. In the 2000s, Ylönen has worked with Teemu Lassila, Alexander Salak and Joni Ortio.

But Ylönen downplays his role in their development. “I’m not sure I’m really coaching,” Ylönen says. “I’m just the goalies’ assistant. I try to give them something to think about. After games, we’ll go over what happened and see how they did compared to what we wanted. We never compare our goalie to the other team’s goalie.”

Ylönen is also careful to make sure the heavy lifting, so to speak, is done elsewhere. The players do a lot of it, but so do the goaltending coaches in the TPS youth hockey system and the Finnish federation’s district goaltending coach.

Until a few years ago, that instructor was Valtonen, Ylönen’s backup in the 1970 tournament. Valtonen is now the goaltending coach of Yaroslavl Lokomotiv in the Kontinental League.

“Producing good goalies is not a new phenomenon,” says Arto Pyykkö, a district goalie instructor in Eastern Finland.

“Finnish goalies have always ranked fairly high internationally. With idols always so close, it’s been easy to attract talented kids to the game, but the thing that keeps them coming is the system set up by the federation.”

In each of Finland’s nine districts, there’s a goalie coach who pays visits to the clubs and supports their coaches by attending practices and organizing training and educational sessions. The structure dates back to the 1980s.

When Pyykkö – now in his 12th season as a district goaltending instructor – comes to town, there can be up to two dozen coaches waiting for him. Half of them are goalie coaches, the rest being coaches wanting to learn more about goaltending, something every coach should know, says Pyykkö.

A typical session takes two full days, often divided into four weekday nights, and consists of 10 hours in the classroom and six on the ice. It’s the passion of people such as Pyykkö, who still has a regular day job as a business consultant, that keeps the factory churning.

In addition to his district duties, Pyykkö also works with the goalies in his local Joensuu club. There, the club has weekly goaltending sessions for three age groups. Each team within the youth system also has its own goalie coach and a club rule states that the goalie and the goaltending coach should get at least 15 minutes of their own time during every practice.

According to Pyykkö, the Finnish style differs a little from the North American and Swedish styles. The Finns have identified 10 ways of scoring in hockey, each defined by the distance of the puck from the net and the goalies are coached to deal with all of them. They’re expected to stand up a little longer than their North American counterparts and to catch or block pucks with gloves or the stick, instead of just staying square to the puck.

“Everything is derived from game situations, we’re deep inside the game,” Pyykkö says. “Then again, different techniques can be taught and learned, but there’s also the X-factor we’ll only see when the puck drops for real.”

And maybe that is in the genes. According to genetical mapping of Europe, Finns are a little different from the rest. And as we know, goalies are a little different, too.

– – – –

* Myllys, Best Goaltender in the World Championship in 1995, comes from the same hometown, Savonlinna, as Tuukka Rask, and played 39 games in the NHL in the early 1990s.

** Twenty years after retiring from the NHL, Takko is still in the Top 10 in NHL games played among Finnish goaltenders, with 142.

*** Mattsson’s claim to fame is that he was the goalie who snapped Wayne Gretzky’s record-long 51-game point scoring streak in 1984.

– – – –

Published in the Feb 17, 2014 issue of The Hockey News