When I moved to Sweden in 1998, I stayed the first week in an apartment that belonged to a friend of friend, before moving into another apartment that I rented from a future colleague. Well, she was already a colleague, but only for a few days. My first week there, I didn’t have any furniture so I spent my nights lying on a borrowed mattress in the kitchen, reading under the kitchen hood light.

No surprise then, that I didn’t have the right cable package to watch the hockey World Championships three weeks later, although I did have electricity and a couch at home. I followed the tournament in the papers, and did watch half of one game in a bar with another new colleague of mine, but didn’t see the final games between Sweden and Finland.

The day after the final, I was sitting in my office across the street from the Royal Palace, trying to decide whether to walk up to Sergels Torg, the square where the hockey team had traditionally had their celebration with the fans. The people.

For a Finn like myself, the square – which is the main subway station in town – had become something of a mythological place, because a few years earlier, when Finland had won their first World Championship gold, the Finnish team had celebrated it at Sergels Torg, an act of invasion, if you will. (Not that the Swedes seemed to mind).

I decided to go. I figured it’d be a good first step in my moving process. Celebrating hockey gold with tens of thousands of Swedes surely would make me feel welcome in my new country.

Also, I really wanted to see Mats Sundin.

I’ve always been a fan of Team Sweden. I think the reason was originally called Mats Näslund, a small winger I could relate to. After him, there was Håkan Loob, Bengt Åke Gustafsson, “Masken” Carlsson, and then suddenly, when I had given up on my dream of becoming a player like them, and instead, was in Turku, Finland during the 1991 world championships to do demos of a hockey coaching software at a coaching symposium, there was Mats Sundin.

In that tournament, he did something not many others could do, which is to skate around the Soviet legend Vyacheslav Fetisov and score the championship winning goal (having also scored two goals in fifteen seconds during the last minute of play in the game against Finland to tie the game), and he was just 20.

The next fall, after a year’s hiatus during which I graduated from the university, I picked up my skates again, and found a new team. That spring, Sweden won another World Championship, with Sundin on the team.

On that team, there was also an 18-year-old player called Peter Forsberg, but I didn’t pay too much attention to him, not until two years later when he scored the shootout goal that won Sweden Olympic Gold. By the time he won his first Stanley Cup in 1996, I had naturally heard of him, and was involved in an ongoing debate with a teammate of mine, who had lived most of his life in Sweden, on which one of them was better: Sundin or Forsberg.

I was firmly in the Sundin camp, he just as firmly in Forsberg’s.

In the end, I decided to walk up the street to Sergels Torg to see what it was all about. The whole team was supposed to be there as well as some entertainers. The square was only a seven-minute walk from our office, on a regular day. The day of the parade was not a regular day as 70 000 Swedes packed into downtown Stockholm.

I can only assume most of them were there to see Sundin, too, but I don’t know that for sure.

I do know for sure that I didn’t get too close to the stage, and gave up a couple of hundred meters from the square, turned around, and went back into the office. I watched the rest on TV instead.

A year later, I met Wife, and getting to know her family who lived in Sollentuna, Sweden, I was happy to learn that Sundin, too, was from the same Stockholm suburb. In fact, my future brother-in-law had once inherited Sundin’s old hockey pants at the local club.

Wife and I moved to Finland, and the next spring, Brother-in-law and I witnessed a classic game between Finland and Sweden. Finland had a 5-1 lead early in the second period – with Sundin scoring for Sweden – and Brother-in-law zipped up his hoodie, to cover the yellow Swedish national team soccer shirt he was wearing in honor of the day. Tre Kronor rallied back, though, making it a 5-4 game after two periods, and a little sliver of yellow was showing under Brother-in-law’s hoodie again.

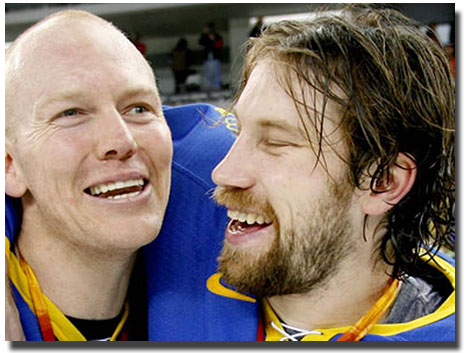

When Forsberg got the puck behind the Swedish net, with 11:49 remaining in the third period, he was eight weeks shy of his 30th birthday, and nine weeks from accepting the Hart Trophy as the NHL MVP. He picked up speed, accelerated through the neutral zone, around the Finnish defence, and around the net, and shot the puck towards the net, where it bounced in and the game was tied. A few minutes later, Sweden scored the game winning goal, with Sundin screening the Finnish goalie, and went on to play in the final. Brother-in-law’s hoodie was off, as he accepted congratulations from Finnish bikers.

But there was no parade that year.

In 2006, Sundin and Forsberg were back together, in the Olympics. They beat Finland in the final, with Nicklas Lidström scoring the game winning goal, the assists going to Sundin and Forsberg.

Wife and I were back in Sweden, expecting Daughter to arrive any day, when Sundin decided to charter a plane and take the team on a detour to Sweden to celebrate with the people, before they all would return to their NHL teams.

The party had moved from Sergels Torg, now deemed a safety hazard, to Medborgarplatsen on the south side of town. This time I got there early, an hour before the sunset, and I found a great spot at the back of the square, on the local swimming pool stairs. As I stood there I saw more and more people fill the space between me and the stage. I saw the women’s team take the stage, and I saw the sun set. I heard the crowd roar and I felt the temperature go down with the sun, but I hadn’t see what I had come to see so I stayed.

And then, almost suddenly, the team was on the stage, wearing gold helmets. I saw Henrik Lundqvist show off some dance moves, and I saw Peter Forsberg dance with Sweden’s Minister of Culture and Sports, Leif Pagrotsky, even if “dance” is an overstatement for what actually happened.

Then Sundin, the team captain, took the stage wearing a golden helmet, and a big smile on his face. My fingers were numb because of the cold, but I waited, and waited until they zoomed on him, then took a photo of the stage and the big screen, and went home.

The weather was gorgeous in May in 2013, the cherry trees in the downtown park had already turned green. Sweden had won the World Championship, and the team once again celebrated the championship with the people, but not at Sergels Torg nor Medborgarplatsen, but in Kungsträdgården, the Kings Garden.

I rode my bike into town, parked in against a tree, and elbowed my way next to the stage and then stood there watching for a while.

But it didn’t feel the same as before. I missed Forsberg and Sundin.

I haven’t had the Forsberg – Sundin debate with my friend in a long time but with both “Sudden” and “Foppa” now in the Hockey Hall of Fame, I think we both should be happy.

I know I am.